About Healing and Hurting: Obama’s health care legacy

This special project, part of WITF’s Transforming Health initiative, came after months of work by the Transforming Health team.

As the future of the Affordable Care Act has reemerged as a topic of debate, reporter Ben Allen wanted to focus on the true impact, not the political rhetoric.

He spoke with dozens of people to get a sense of how the Affordable Care Act has affected their lives, both positively and negatively.

These stories stem from those conversations.

There were many interviews that did not make it into the series, but they all informed the final product.

Additionally, his reporting has been informed by off-the-record and on-background sessions with those in the health care industry.

Transforming Health is funded by Penn State Health and WellSpan Health.

The project is led by WITF Senior Vice President for Content Cara Williams Fry.

Stories were edited by WITF’s Multimedia News Director Tim Lambert.

Design work by Tom Downing.

For more stories like this visit transforminghealth.org

For Harrisburg lawyer with MS, Obama’s health care law has been vital

Ben Allen, Transforming Health reporter

Scott Caulfield is a familiar face in the halls of his oncologist’s office in Harrisburg.

“Oh hi, how are you?”

There’s a familiarity to his greetings.

He casually chats with nurses, office staff, even people in the waiting room that he recognizes from his frequent visits.

“…yeah, I know, I know, I’m slowing things down…”

This is all routine for him.

One nurse asks if there’s anything new to report.

His answer?

Everything is the same.

But that masks a much more complicated story that started one morning in 2015.

He woke up and he couldn’t walk.

He tried to get moving, but nothing would work.

An ambulance got him to the hospital, where he ended up staying for a week.

After a week there, he was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis.

“I thought, wow, done at 39. I thought I was done. I thought I wasn’t going to be able to walk again,” he says.

That was his lowest point.

Since then, he’s established a rhythm.

13 times a year, he visits this office to get his usual treatment: an IV drip of the drug Tysabri.

“Thankfully, MS is non-fatal,” he says. “It is however chronic and there is no cure for it. It is something I will have to deal with for my entire life.”

Since he was first diagnosed with MS, he’s progressed from a walker to a cane.

He still runs his own law firm, focused on regulatory matters, and he also worked on Governor Tom Wolf’s campaign team.

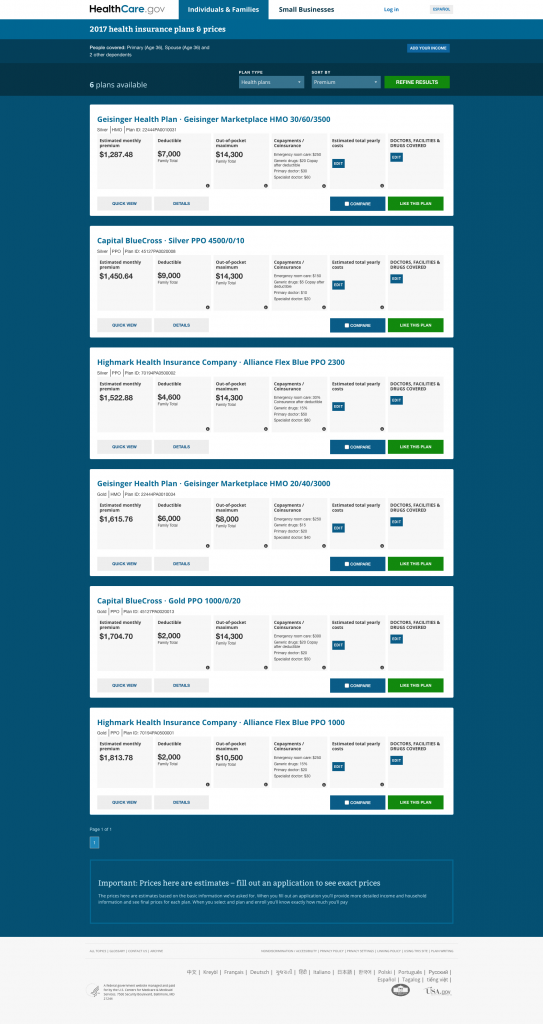

Caulfield buys insurance on healthcare.gov, also known as the exchange.

In 2017, he’s going to pay about $7,000 in premiums.

“I experienced a 42% increase in my premium for this year. I’m not happy about that, but I accept it. That’s what happens,” he says.

Now, Caulfield can afford to pay for that kind of increase thanks to his work as a lawyer.

But he also accepts the hike because he knows his care is costing the insurance company a lot of money.

“[He] is going to cost us $150,000 in a good year,” he says out loud, imaging a conversation among insurance executives in a boardroom.

“And he’s going to pay in premiums, maybe $7,000.”

In a world without the Affordable Care Act, they might deny him full coverage. He could face a waiting period of 6 to 12 months, where he would have to figure out how to pay for $150,000 in treatment out of pocket. And even when he got on a plan, some treatments might have required him to pay more out of pocket.

But the ACA requires insurance companies to cover everyone, no matter their pre-existing condition.

So when Donald Trump won the presidency, with his pledge to repeal and replace the ACA, Caulfield’s mind started racing.

“I started looking around on November 9 when I woke up. I thought it’s a possibility now and I’ll have to start calculations tomorrow morning,” he remembers.

He says every day, he reads about what is happening on Capitol Hill.

He even watches Senate deliberations on CSPAN.

Yes, CSPAN.

Sure, he was already paying attention, but now that it affects him, he’s obsessed.

Caulfield has even looked at other states – New York and New Jersey among them – that have protections in their laws to guarantee coverage.

He’s also considered shutting down his private practice and going to work for a bigger firm, so his can receive insurance.

But despite all the uncertainty about his future, he says he tries to keep things in perspective.

He says, “There are far better people than me, who deal with far worse situations, and I try not to feel sorry for myself.”

Caulfield says he’s speaking up for those who can’t.

One in six people in the U.S. have a pre-existing condition: anything from epilepsy to severe obesity to sleep apnea.

Most get coverage through their employer, but some shop on the exchange like he does.

Providing coverage for those in need means people in good health have to pay higher costs than they might normally expect.

That’s how insurance works.

It’s a similar concept for home insurance: homeowners with houses that don’t suffer damage from flooding or fires subsidize those who have issues, but keep their insurance as protection in case that fire hits their home.

Caulfield speaks from experience: “Soon, you’ll be that guy who needs it, who needs the health insurance. You’re not going to be Peter Pan and not grow up. Life happens.”

Caulfield’s visit wraps up.

That’s one down, a dozen more to go in 2017.

Every day, his MS affects his life.

And every day, he wonders how decisions made on Capitol Hill might leave him without access to the care he needs in the future.

For more stories like this visit transforminghealth.org

Healthcare.gov prices: great for some, frustrating for others

Ben Allen, Transforming Health reporter

When you talk about the Affordable Care Act, the conversation inevitably lands on healthcare.gov, also known as the exchange.

It’s one of the most controversial parts of the law.

When it debuted, technical problems made it nearly impossible for millions of people to buy health insurance.

And recently, insurers have hiked rates for plans on the exchange by double digits, with some increases approaching 50 percent.

For some, the cost is impossibly high.

But for others, it’s worth it.

Dusty Malesich and his wife Julia James run a stand at Harrisburg’s Broad Street Market, a bustling place filled with places to buy fresh fish, homemade pizza, sandwiches, pierogis, baklava, popcorn and so much more.

At theirs, called Radish and Rye Food Hub, they sell local meat, vegetables, bread, milk and other goods.

“Oh yeah, it’s way more than a full-time job,” says Dusty, even with the stand only being open three days a week.

Before the Affordable Care Act, Dusty – who used to work in construction – went without insurance.

And Julia received coverage through work, but then shifted to part-time to run the stand…so she wasn’t covered.

That means for a couple of years, they’ve shopped on healthcare.gov.

“This year, we’re looking at $500,” says Dusty. “It doubles, hangs there for a minute, then doubles again. It feels very out of control to me.”

That’s for two people, who expect to make about $60,0000 this year.

And the price tag includes their subsidies through the exchange.

“We do fine in life, but it just doesn’t feel like we have that kind of money,” Dusty adds. “It just feels like, I don’t know how normal people do that. It’s by far our biggest expense.”

Both of them are pretty healthy people.

Dusty has only been to the hospital for stitches because of his construction work, and Julia couldn’t think of the last time she needed serious care.

“I don’t think we’ve come close to using up our deductible. Even if we do go to the doctor more often than normal, it’s still, the only way it could help us is if we hit by a bus or got cancer or something,” he says.

Because of that, they don’t want insurance that covers everything, things like maternity care or routine doctor’s visits.

Julia – who worked as a benefits manager – knows her way around the health insurance world.

But even she couldn’t find a plan that would work.

They just want one that would provide a safety net if they had to deal with a catastrophic event.

She says: “It does seem like they eliminated some options that would be a good fit for our situation, that are just no longer available.”

And it’s true – the Affordable Care Act has hurt them.

As is usually the case, big policy changes leave behind winners and losers.

For the 415,000 Pennsylvanians who buy on healthcare.gov, premiums jumped an average of more than 30 percent from 2016 to this year.

For healthy people like Dusty and Julia who aren’t going to the hospital or visiting specialists on a monthly basis, it’s particularly difficult to swallow those increases.

But – and here’s a reminder of how insurance works – Dusty and Julia, and other healthy people, help make costs more reasonable for sick people like Tracy Reever.

Reever’s a full-time nanny for a family in Lancaster County.

She’s the one keeping an eye on a two-year-old, and a six-month old.

“Are you going to be shy? Oh, you’re going to get the microphone? Want to play with those keys?” she coos.

“She’s a really good baby. She loves to just lay down and look up at you. We sing songs, and yeah.”

Tracy is just like Dusty and Julia – she works for herself, so she has to buy health insurance on her own.

But her medical history is much different than theirs.

“I was diagnosed with Crohn’s disease in 1998, my freshman year of college,” she says.

“Maybe 3 years after my Crohn’s diagnosis, he diagnosed me with something called sarcoidosis, which is super rare. But basically, my body was attacking itself. Then, about a couple months after the sarcoidosis came under control, they diagnosed with cardiac myopathy.”

Because of her health history, when Reever graduated from Penn State in 2001, she had to pay $849 a month for health insurance.

“It was a shock to try and figure out how I was going to pay for that every month and pay the monthly bills that would roll in,” she says.

Remember, this was back in the days before the ACA, when someone couldn’t stay on their parents’ plan until age 26, and companies could charge higher rates based on your medical history.

Reever says she was spending about $1,000 a month on health care.

But then came the Affordable Care Act.

“I remember going into their house that morning and saying, oh my gosh, do you know what my new insurance premium is going to be? It was under $300 for a much better plan,” she says.

She still gets all her prescriptions, and makes all her doctor’s visits.

But her costs are much lower.

Some of her family members had been skeptical of Obamacare from the start – after all, they were hit with some of the downsides of the law.

But she says, she reminds her dad she no longer has to ask to borrow money to pay for prescriptions.

“For years, I just paid it because I knew I had to. I didn’t have a choice. And no one cared. I felt like no one cared when I was paying it. But I’m also not a complainer. It was what it was, and I had to pay it, and I needed health insurance, so I made it work,” she says, with a sigh.

Reever says she knows for those who have seen their premiums double, that reasoning isn’t enough.

People like Dusty and Julia, from the start of this story.

“It doesn’t feel right to me. It feels like once we get to the age that we’ll be consuming a lot more care, it feels like we’ll have paid in way more than we could possibly consume” says Dusty. Julia continues: “And at that, we’ll be paying more because we’re older.”

Most would admit something needs to be done to improve Dusty and Julia’s situation.

But what kind of changes could be made, without hurting people like Tracy Reever?

After all, she’s no longer drowning in medical bills, so she’s been able to buy a little house in York County.

However, with changes expected to the ACA, Reever says she’s starting to think about leaving her dream job as a nanny, the one she’s most passionate about, to work in a corporate office – because they would have to provide her insurance.

For more stories like this visit transforminghealth.org

Coverage through Medicaid expansion has been vital for York man

Ben Allen, Transforming Health reporter

More than 700,000 low-income Pennsylvanians now have health insurance through Medicaid expansion, which is part of the Affordable Care Act.

Nearly half who have enrolled say they have a job.

About 60 percent are white.

But numbers are one thing.

You’ve probably heard stories about how Medicaid expansion has helped people.

But Kim Altland’s story is a unique one.

“You’ll have to excuse me, I’m a little faster coming up than it is going down”, he says, as he makes his way down the creaky stairs to the basement of his grandfather’s house in North Codorus Township, York County.

He reaches the bottom, and points.

“Back here behind the steps is my bed area”.

It’s dark and damp.

There’s a single light bulb on the ceiling, and Kim’s desk – filled with all kinds of papers – is tucked in the corner.

“Learning has been kinda a lifetime passion for me,” he says. “Right now, I’ve got two different books I’m reading. One’s a manual on a programming language called Python. And the other one’s this one, it’s called the Idiot Brain. “

The basement has been his home for three years, after he lost his house and his job.

He’s got a van parked out back, but he can’t pay for insurance, so his mom Carol Landis gives him rides to all his appointments.

As she says, “I can’t afford to pay to have him on my insurance as an extra driver, and there are times where he needs help, so I just bite the bullet and do what I can.”

Landis lives upstairs and is herself surviving on Social Security.

But her story can’t match Kim’s.

He was born a conjoined vestigial twin – his brother died at birth.

Altland has had surgery after surgery ever since.

“Somebody asked me once, Well when did the pain start?, and I cannot remember a time in my life when I did not have some kind of pain,” he says.

“When I was younger, it was easier to just ignore it and work through it, but that doesn’t happen anymore.”

As if he needs to prove it, he pulls out a crinkled Ziploc bag full of wristbands.

They pour out, covering the coffee table.

His early years were truly extraordinary.

Altland initially had a double pelvis, so doctors had to break them and rewire the pieces together.

He’s been in at least 5 body casts.

Even after all those surgeries, he walks with a noticeable limp, despite special shoes.

Still, he’s persevered.

Altland worked for at least 20 years, in printing, electronics assembly, and retail.

But then, he was laid off in 2011, and he lost his health insurance.

“It was definitely deteriorating. There was no holding ground,” he says. “That was the time when I started having the worst problems with my urethra, started having bladder infections and I was unable to get medicine.”

Altland was just barely holding on.

Because he was so poor, he only had one option.

“I’d show up at a hospital or emergency room and say I need care. It was kind of piecemeal. I never knew what kind of care I was getting,” he remembers.

It was free, with either the hospital or taxpayers picking up the bill.

But it wasn’t the kind of care Altland needed to get better.

He hasn’t been able to work a full-time job because of his health, and social security has already denied him disability benefits once – which is common.

His luck changed in early 2015 — when Governor Tom Wolf expanded Medicaid through the ACA.

“I was able to get a new full-time doctor who could look at my case. That really helped. So I started getting medical care, was even able to go to Hershey to get some surgery,” he says.

For someone whose income was about $5,000 last year, it was a godsend.

He can get his prescription medicines, urinary catheters, and orthopedic shoes.

He can visit specialists like his urologist, orthopedist, and others, on a regular basis.

And, he can go to group therapy.

Along with the Commonwealth, 30 states have expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act.

The move has given low-income people a chance to receive insurance and get the care they need.

Before the ACA, in most cases, you had to be more than poor to get help.

You had to be poor and pregnant. Or poor and disabled. Or poor with children.

Altland’s mom Carol has noticed the difference since he signed up.

“I think there’s been a less fast decline and it’s made him a happier person,” she says, simply.

And it’s had an impact on her life too.

“Less visits to the doctors, and less chauffeuring duties,” she laughs.

To be clear, Kim Altland’s story is not the typical story of every person on Medicaid.

In fact, some are certainly healthy.

But state statistics show nine out of every 10 people who signed up through the expansion have used the coverage to see a doctor.

Kim says: “I had the appearance of managing fine, and a lot of people do. Even under the ACA, when you have access to resources, even if all needs aren’t being met, look better than you may actually be. And I think there are a lot of people in that position.”

Altland is still looking for work.

But in his eyes, at least he has health insurance.

Republicans talking about repealing the Affordable Care Act, which would end Altland’s Medicaid coverage, has made him anxious.

So anxious, in fact, that he’s applied for a passport so that if he loses insurance, he can go to a country that can provide him the help he needs.

For more stories like this visit transforminghealth.org

Lancaster County business is fed up with the Affordable Care Act

Ben Allen, Transforming Health reporter

The Affordable Care Act has faced formidable opposition, and some of the loudest complaints have come from the small business community.

Groups like the conservative National Federation of Independent Businesses have led the charge, suing to stop the law when it was first signed by then-President Barack Obama.

The case eventually made it to the Supreme Court.

But, that opposition has not died down over the years.

Cheryl Hendrickson runs Detailing Technologies in Manheim Township, Lancaster County with her husband Dan.

It gets especially busy on Thursday’s – most of their clients are wholesalers who are headed to the Manheim Auto Auction Friday morning.

Since the shop opened in the late-1990s, Hendrickson has managed the benefits for her and Dan and their 14 employees.

Back then, she says they offered health insurance that cost less than $40 a month for a family of five, with no deductible and a $100,000 life insurance policy attached.

Premiums had been increasing far before the Affordable Care Act, with families in Pennsylvania paying, on average, 65 percent more in 2011 than in 2003.

But Cheryl says the ACA created a mess.

“In 2013, our group health insurance was cancelled by the provider,” she says. “We received a letter in the mail, and said by interpretation of the Obamacare Act, your health care has been cancelled. We looked at other group policies, the rates went up 35-60%. Employees didn’t want insurance at those rates.”

Hendrickson says the provider determined the policy didn’t comply with the law’s requirements.

Since then, evaluating health insurance options has taken up more and more of her time.

When open enrollment rolls around every year, she says she looks at choices for herself and the business.

This year, she went outside the box.

“I’m on a short-term policy that can run up until 11 months. They don’t cover pre-existing conditions, prescriptions. It’s more a catastrophic plan,” says Hendrickson. “I mean think about it, do you need health insurance to go to a doctor?”

The policy doesn’t meet the requirements of the ACA, but Hendrickson says it’s what she wants.

Since the business has less than 50 employees, it isn’t required to provide coverage.

“We tell them that we do not offer health insurance, that our group plan was dropped by interpretation of the Obamacare Act, and we have never been able to find insurance at a reasonable rate,” she says.

The conservative National Federation of Independent Business says Hendrickson’s experience is common, pointing to a survey of its members that found widespread premium increases.

But such hikes were coming before the ACA existed.

And some other small businesses like the law.

Hendrickson often finds herself just as frustrated with other parts of health care reform.

Up until recently, an IRS regulation blocked businesses from helping employees pay insurance premiums tax-free.

So, Hendrickson came up with a work around, paying for some doctor’s visits, and giving some raises.

“I would very much like an affordable plan that I could offer my employees. That would be the top of my wish list for our company,” she adds.

More than once, Cheryl called the ACA as a disaster, or the Unaffordable Care Act.

But her perspective comes from a distinct place.

She’s doesn’t really think health insurance is necessary.

She says she managed to go without it until she turned 40.

“I called the hospitals, I called the doctor, I said what’s your price, they told me their price, I saved my money, I paid in installments, and paid for my children to be born,” says Hendrickson.

Cheryl is healthy, and says she only takes one prescription.

To get costs down, she would rather see different options for small businesses.

“I know you can’t always know what the future brings, but I think maybe an a la carte health care plan. There’s certain things in my life I know I will never deal with, like because of my age, pregnancy. Mental health is something I know I will never deal with,” she says.

But those kinds of plans defeat the point of health insurance.

People don’t know if they’re going to be diagnosed with cancer, or need mental health treatment, or come down with a serious case of the flu.

The same principle applies for car insurance — it’s required by state law, but few buy it expecting to have to use it – it’s about protecting yourself.

To have a strong insurance market, small business owners like Cheryl need to sign up for coverage, something she doesn’t seem anxious to do.

“Well I still have a lot of trust and faith in God. That pulls me through.”

Hendrickson says some of her employees go without coverage, skipping sign ups on healthcare.gov.

She’s put her faith in President Donald Trump to make a difference.

But pulling on one string in the health care world could unravel many others — whether they are small business owners, someone diagnosed with a chronic, lifelong condition, or a family whose baby has to spend a week in the NICU after entering the world.

For more stories like this visit transforminghealth.org

Harrisburg woman has benefited from the ACA. But her mom has been hurt by it.

Ben Allen, Transforming Health reporter

Every big policy change helps some and hurts others.

Some on the left would like you to believe that the Affordable Care Act is nearly perfect.

And some on the right would like you to believe that the ACA has only hurt people.

The truth is somewhere in the middle.

Kate Moyer lives in midtown Harrisburg with her husband Cody and their two dogs – Rosie and Ruby.

Moyer, a Democrat, is in between jobs right now – she’ll soon be working as the marketing manager at the Capital City Mall.

She says she’s been pretty healthy and tries to take care of herself.

“I was a runner for about a decade, starting in college. Life kinda got in the way after that,” she says.

But late in 2013, Kate was struggling — not physically, but mentally.

“I was in a really, really bad place,” she says.

Moyer says she was fighting through a particularly low point, brought on by depression and anxiety…

“I was suicidal, I was agoraphobic, I couldn’t leave the house. I wasn’t practicing greats self care,” says Moyer.

The dark moments came just as she was transitioning out of full-time work, where insurance was provided.

So, she was faced with having to shop for coverage.

It was also just as the Affordable Care Act, and healthcare.gov, were about to take effect.

Moyer says it was a bit overwhelming for someone who wasn’t really familiar with deductibles, out of pocket costs, and narrow networks, but she was able to get affordable coverage.

“When I think back now, about Oh my god, what if? it’s a scary though,” says Moyer. “And I know my family was worried about me at that time, and my friends, and everyone was really concerned. And we’ve all said at one point, thank God that you had health insurance.”

It’s important to be clear here.

Before the Affordable Care Act and healthcare.gov, Moyer would still have been able to get health insurance.

But considering her pre-existing conditions, she likely would have had to pay far more than the prices under the ACA in 2014, and that type of insurance may not have covered everything she needed.

The insurance covered her visits to a therapist and medications for the depression and anxiety, plus regular blood tests for her hypothyroidism.

Prices have kept rising since Obamacare took effect, but she says it’s helped her.

But her mom has had a much different experience through the ACA.

“I think it’s really unfortunate that that costs have risen so tremendously,” says Moyer.

Kate says her mom pays about $500 a month for insurance coverage as part of the Affordable Care Act, even though she’s relatively healthy too.

To her, that doesn’t feel right.

“I think that’s outrageous, to take care of somebody who for the most part, is a healthy person. That seems like an extreme amount of money to me,” says Moyer.

Moyer has hashed out the impacts of the ACA with her mom, highlighting how it has helped her.

But go back to the $500 a month her mom pays.

“It’s hard to reconcile that. That we have people who are pushing their budgets or exceeding them in order to afford health insurance who may not really need it as much as someone else. That’s a rock and a hard place,” she says.

“I don’t think it brings comfort to people,” adds Moyer.

Before Obamacare, healthy people may have purchased a catastrophic plan, taking the risk they would really only need insurance if they were diagnosed with a chronic condition, like Crohn’s Disease, Multiple Sclerosis, or cancer.

Now, they usually have to either pay a fine for not having insurance, or pony up for more expansive coverage that they don’t want.

“It makes me upset, actually,” says Moyer. “I don’t feel like anybody should have to choose, I don’t think anybody should have to even consider that. Do I want to potentially take on $20,000 worth medical debt in a catastrophic incident or do I want to maybe stretch my budget and sacrifice on some potentially essential things to meet my health insurance premium every month?”

“What kind of a choice is that?” she asks, her voice rising. “That’s not really a good choice in either direction. I don’t care what side of the political spectrum you sit on.”

Moyer’s story is one that shows there’s more to the law that supporters or detractors want you to believe.

It’s helped some, and hurt others.

If Republicans want to scrap the law, they face more than a handful of challenges.

Think, for a moment, about a Rubik’s Cube.

6 sides, 54 tiles.

You feverishly work on one side, getting all the reds together.

You look up and are ready to celebrate.

Then, you remember.

There are five more sides.

Green, yellow, blue, white and orange tiles are all jumbled up.

Sounds a bit like health care.